This memo is transcription from l’Observatoire du Long Terme, followed by a personal digression about the role of the architect in scale ups.

Learning from Manhattan urban planning Link to heading

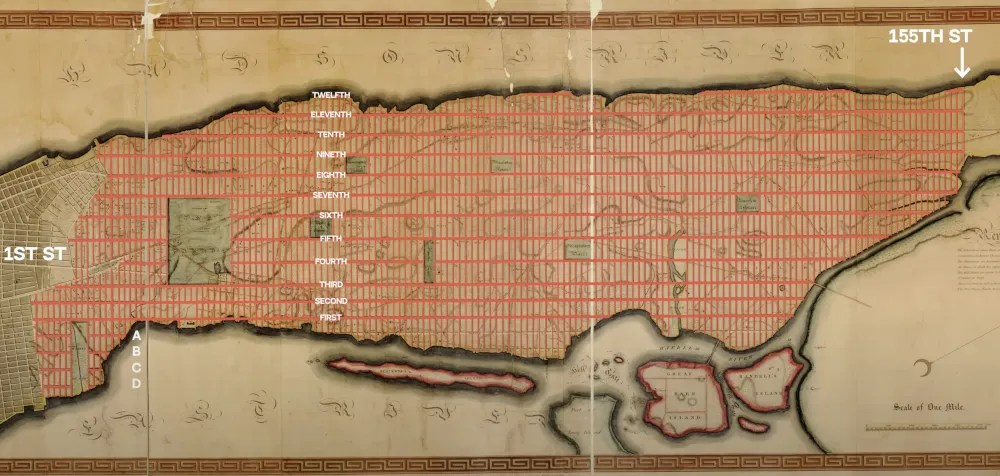

The narrow, irregular streets of southern Manhattan — with unpredictable names and intersections at all sorts of angles — starkly contrast with the rest of New York, grid‑like with streets (from First to 220th) and avenues (from First to Twelfth) that are broad and intersect at right angles.

The explanation is historical: there was no urban planning at the start of the 17th century when New York began to serve as a Dutch trading post. The streets followed paths taken by inhabitants or were added as needed, without a comprehensive vision. Traveling there is more difficult (especially for foreign visitors), public works are harder to plan, and the city’s growth is harder to organize.

The south of Manhattan was laid out by plumbers (who dealt with immediate needs) whereas the rest of New York was designed by architects (inspired by a long‑term vision of transit needs, and a concern for simplicity and overall efficiency).

Digital Systems Link to heading

The same applies to administrative systems. Some are designed to optimize users’ time at the cost of additional architectural effort. Others minimize the effort of rule-makers by accumulating formalities and incoherent texts, like a plumber running from one leak to another.

Singapore dominates the first category by adopting an engineering approach, which aims to design and manage public policies in a way that maximizes efficiency for users. Every new regulation must demonstrate sufficient benefit, and existing regulations undergo regular efficiency reviews designed to optimize them and eliminate them when they are no longer necessary. Functional architecture rules are imposed to optimize the efficiency of texts and procedures for users. These include common data standards, widespread use of pre-filled forms (relying on standard data), and the mandatory use of common software components (for example, for payment or data collection).

The agency in charge of digitization plays a key role as chief architect and relies on functional architects in each ministry responsible for implementing the standards. Digital technology is often a factor in simplifying or harmonizing processes: it is when digitizing procedures that the cost of excessive diversity in these procedures, or in the information and documents they require, becomes apparent. Before digitization, this complexity is borne by the user. By digitizing, the cost of this diversity becomes apparent, as does the benefit of harmonizing divergent processes from one department to another.

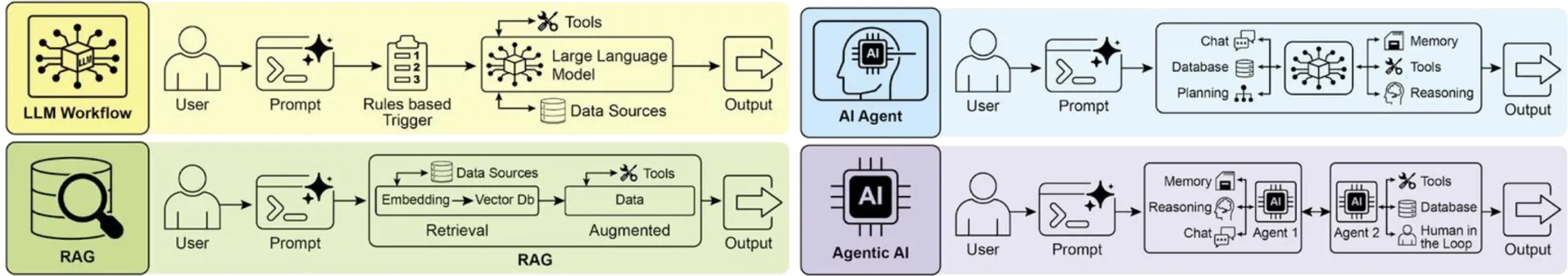

(image credits: Agentic Design Patterns)

(image credits: Agentic Design Patterns)

The normoscope Link to heading

In France, companies and users suffer one of the highest “time‑taxes” of administrative complexity in Europe, which the Observatoire du Long Terme estimates at 6 GDP points (~€170 billion). Past simplification initiatives have often been one-off efforts, whether through reviews (usually escaped by new texts) or the rewriting of legal codes (usually later amendmended with additional complexity).

Two pathways could give more scale to such an effort and embed it over the long run. The first would be to restructure administrative production by introducing architectural principles inspired by SW/IT urbanisation and a user‑centric approach (vs administration‑centric approach), as Singapore has done.

The second would be to evaluate the “time‑tax” and set a target — for example, a reduction of 50 billion. One could start with limited means — for instance by sampling time spent on the top 100 main formalities. A collaborative tool, the “normoscope”, could also allow users to share flaws in the procedures they face. Given that French households’ means are more constrained than ever, we need to free them from burdens that do not beneficially contribute to quality of life.

When it comes to administrative complexity, that means more architecture, less plumbing.

Digression: Organizing complexity in scale ups Link to heading

I’ve often wondered why some startups manage to grow into successful scale-ups while others struggle. It usually comes down to having the right person in the right role. To make that happen, it’s important to understand what architects are actually supposed to do.

Think of a startup like a restaurant that serves soup. The first soup was a big hit, which helped the business grow. As the restaurant expanded, more cooks joined, more recipes were added, and things got more complicated. With each new cook and receipe, the kitchen slowed down. To fix this, the startup founders decided to set up a project management office (PMO) to get things back on track.

The PMO team soon saw that something important was missing: a clear plan for how the kitchen should run. They tried to fix this by giving each cook specific responsibilities, organizing tasks with detailed tickets, and making a master plan based on estimated effort. But none of it worked. The PMO couldn’t figure out why. Everything was written down, so why wasn’t it working?

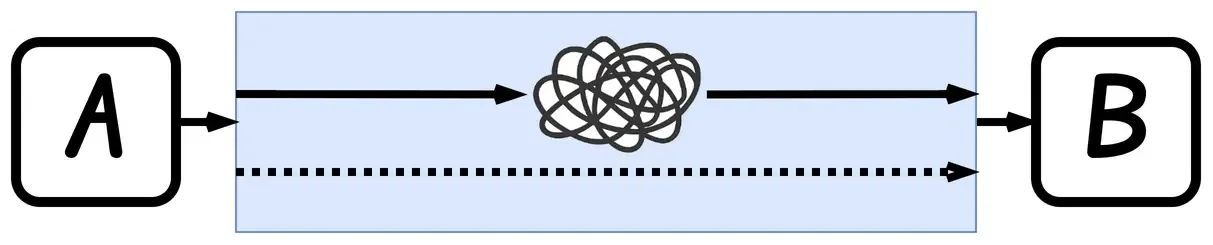

The problem was that the book explained how to make soup, but not what the soup should be. The PMO didn’t realize that they weren’t just making one soup anymore—they had a broth that could be used to create different dishes, depending on what the product makers (PM) wanted. Instead of solving the real issue, the PMO just added more processes, like building more roads without a plan.

What the PMO really needed was a well-designed system that would let everything run smoothly, and scale over time, just like the roads for noth Manhan. PMO’s mistake was not seeing that they needed an architect to create the blueprint of the plan they should be using to organize complexity.

In many scaleups, there is only an engineering director, who not only designs the architecture, but also get responsible for ensuring the team’s growth mindset. The goal is empower the teams to take ownership of the efficiency, rather than imposing it. Only once this steps is reached, one is ready to scale-up!

,

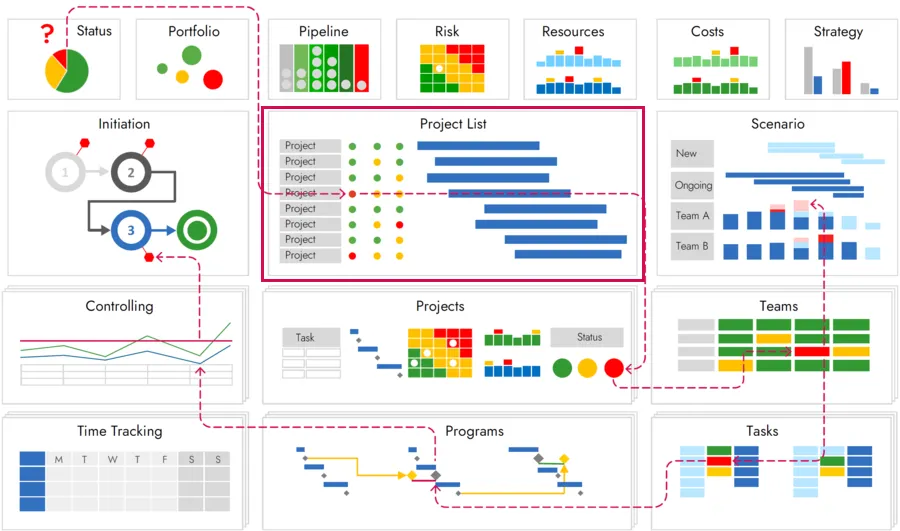

Is the diagram above showing how well the kitchen is designed and organized? Or just how effective it can be operated and turned into profit by PMO ? (image credit: )

Is the diagram above showing how well the kitchen is designed and organized? Or just how effective it can be operated and turned into profit by PMO ? (image credit: )

References: Link to heading

The Observatoire du Long Terme is dedicated to analysing long‑term economic, social, and environmental issues, with the aim of giving more visibility to these issues in public debate. It is independent, receives no financial aid, and relies on the voluntary engagement of its contributors and board.