When compiling for NVIDIA GPUs, CUDA is often considered the reference compilation framework. But how is the compiler actually working? What kind of Instruction Set Architecture, or ISA, does the compiler need to generate when creating an “executable” for the GPU? And how is the compiler actually working? What kind of architecture is used to generate code that can be launched from a CPU and executed on a GPU?

This Sunday morning memo aims to be a high-level overview of the NVIDIA GPU compiler architecture. It covers the GPU instruction set, the NVCC compiler in the CUDA framework, and, finally, alternative architectures that target the GPU instruction set.

Low-level GPU architecture Link to heading

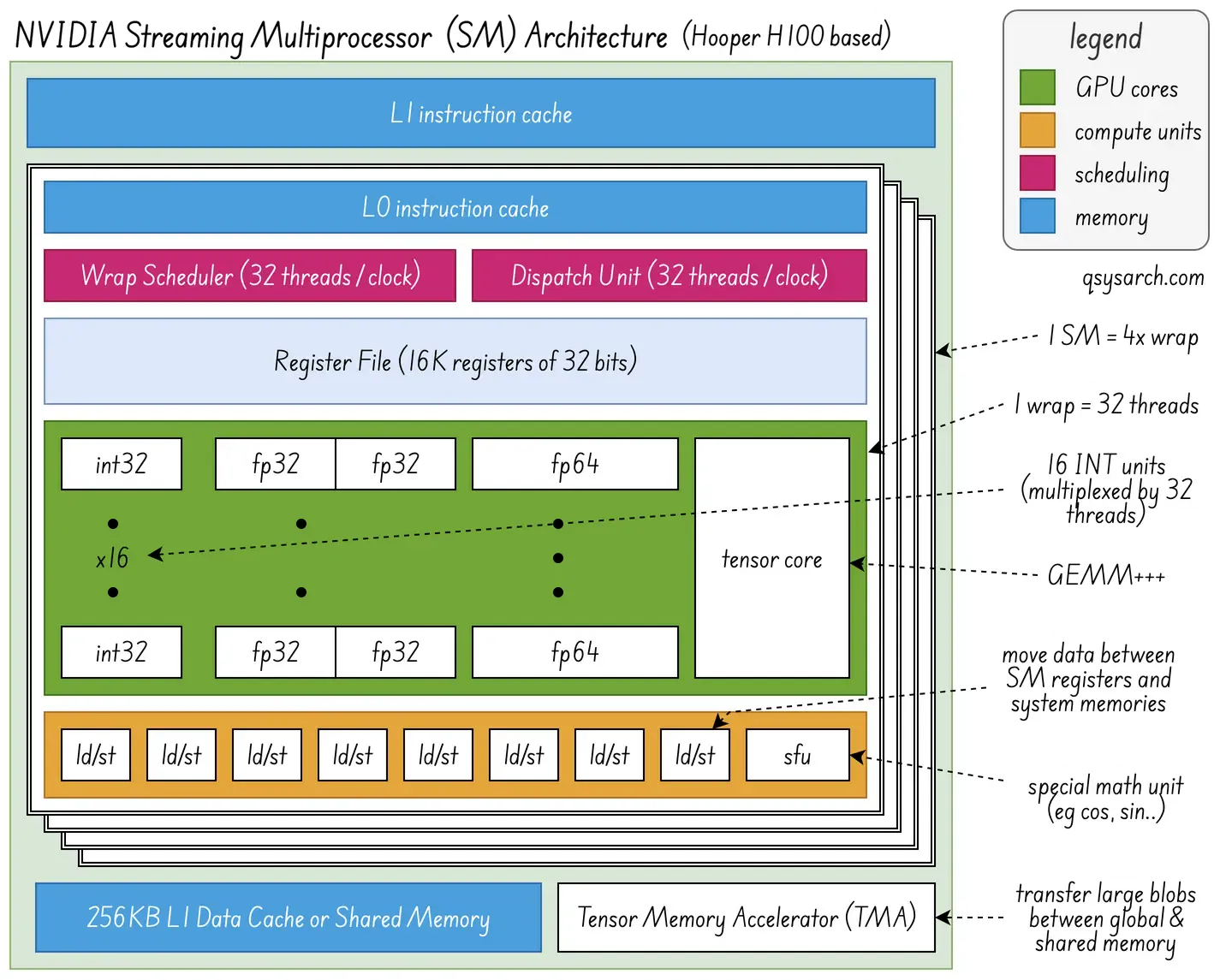

When targeting a device like a GPU, we need an instruction set to program it. In the case of NVIDIA, this device is the streaming multiprocessor (SM) is represented in the diagram on the right. What is interesting in the diagram is that there are many concurrent units, such as the IN32 adders, the special function unit, the GEMM+++ tensor core, and that the compiler should make sure that they are used (pipelined) in the most efficient way (where efficiency is defined as minimising idle time).

This is the terminology in use:

- ISA (Instruction Set Architecture): set of instructions.

- Machine Code: Compact and binary representation of the instructions

- Assembly (langugage): less-compact textual representation of the instructions

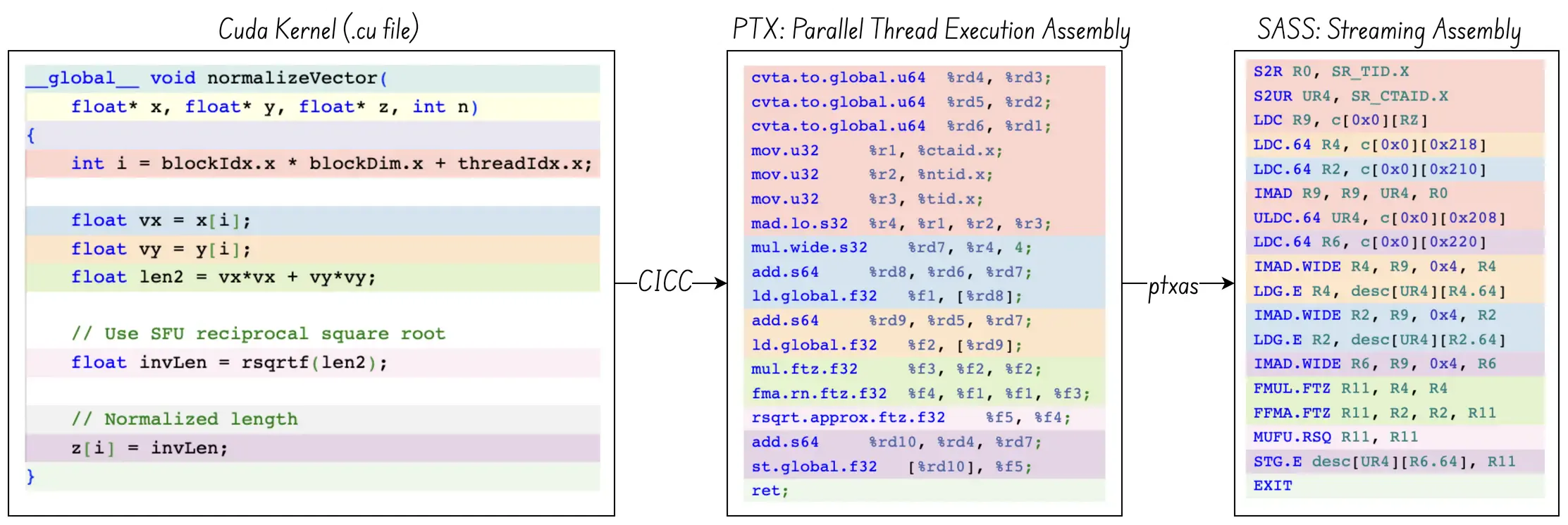

There are two ISAs for NVIDIA GPUs:

- PTX: Parallel Thread Execution - Intermediate assembly used when compiling Cuda kernels.

- SASS: Streaming ASSembly. Lower-level assembly, specific to each GPU architecture

Let’s consider that we want to compile this kernel:

__global__ void normalizeVector(float* x, float* y, float* z, int n)

{

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

float vx = x[i], vy = y[i];

float len2 = vx*vx + vy*vy;

float invLen = rsqrtf(len2); // Use SFU fast reciprocal square root

z[i] = invLen; // Normalized length

}The magic here is that rsqrtf should be dispatched to the SFU pipeline. How does this work? The line float invLen = rsqrtf(len2); is converted to PTX as rsqrt.approx.ftz.f32 and then into SASS as MUFU.RSQ as shown on the picture below from godbolt.

MUFU stands for multi-function unit, also known as SFU, the special function unit. The MUFU.RSQ sends the register through the Root Square “pipeline” of the SFU unit. There are many other instructions in the SASS assembly, such as FMUL (Fused Multiply) or FFMA (Fused Multiply and Accumulate), which are instead dispatched to the tensor core unit. The dispatch unit is responsible for sending the instructions to the right pipeline unit.

There are three things worth noticing:

- The tensor is core much more than a General Matrix Multiplier (GEMM): For example, it can do reduction operations (sum, min/max, dot product) via an MMA (matrix multiply-accumulate) unit inside the tensor core.

- The difference between an

INT32unit and a register: The unit is responsible for the computation (eg, ADD, SHIFT, XOR, … or more generally arithmetic operations, or ALU) while the second is reponsible for storing values. - there are only 16

INT32units, but 32 threads. This is not a mistake: the reason is that the warp scheduler will toggle between two threads set each cycle. So, in cycle 0, the units will perform ALU operations for threads 0..15, and in cycle 1, for threads 16..31.

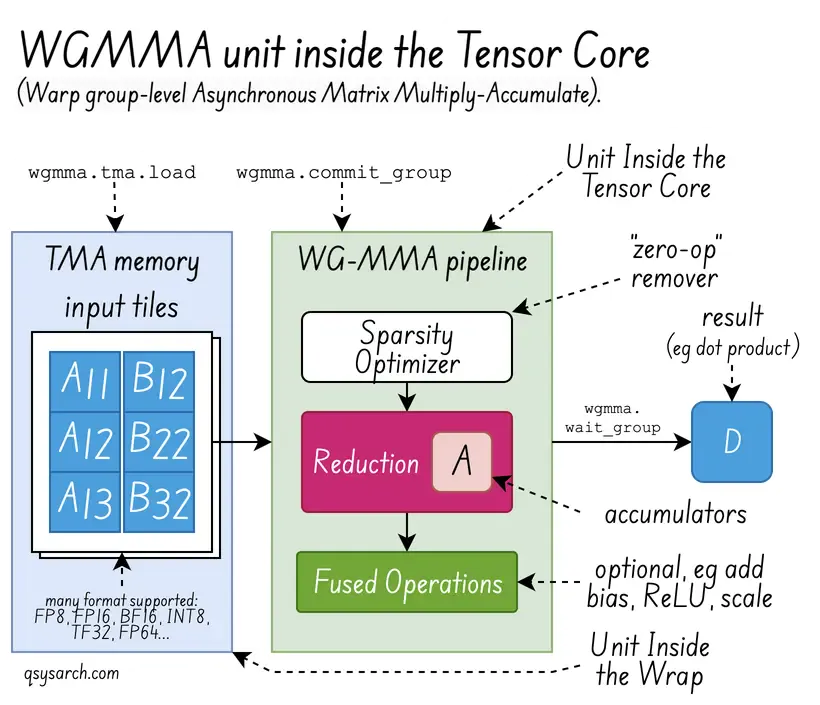

The Asynchronous Warpgroup Level Matrix Multiply-Accumulate Instructions (WGMMA) are pretty powerful. You can read more on the NVIDIA doc as well as in the fantastic blog from Aleksa Gordić.

NVIDIA CUDA Compiler Architecture Link to heading

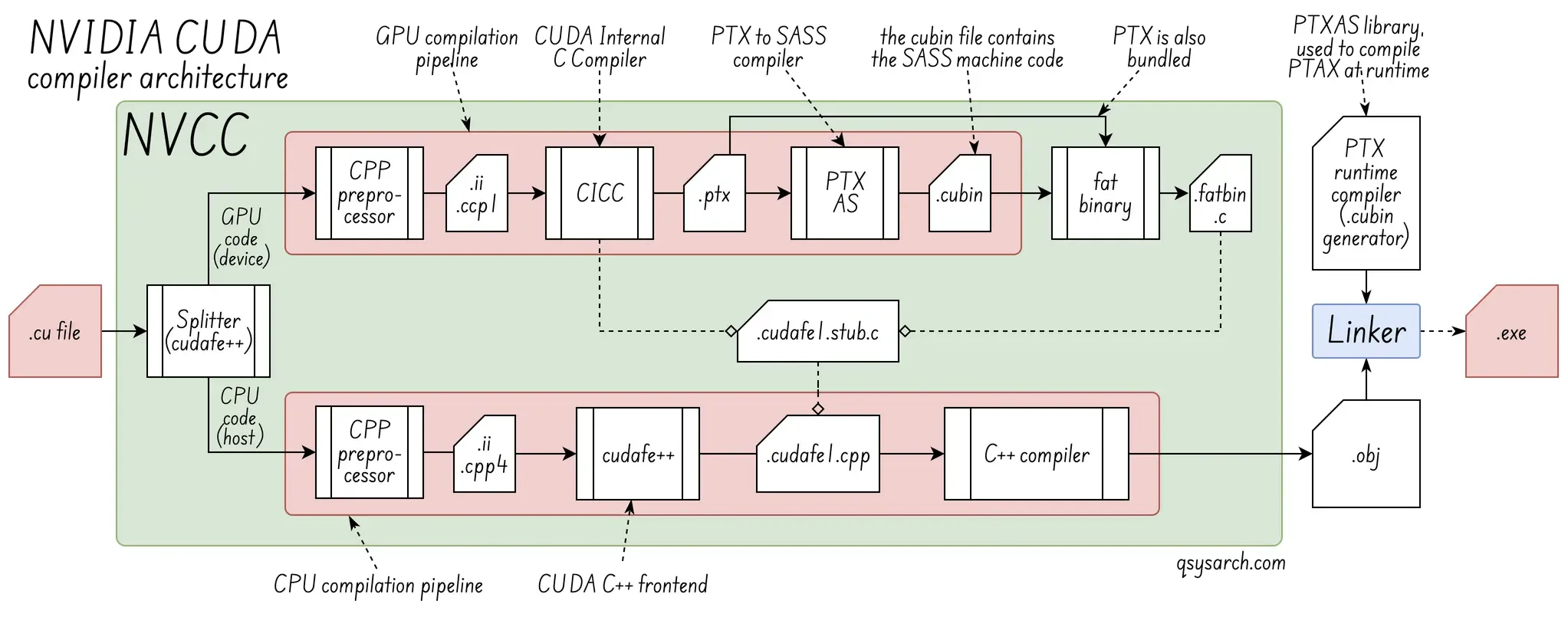

Now that we understand a bit more about the GPU’s low-level ISA for programming the GPU streaming multiprocessor, let’s try to understand how high-level C++ kernels are compiled to SASS. We know that the compiler used to convert CUDA kernels (.cu files) to PTX is called NVCC.

So, what is the difference between NVCC and LLVM? NVCC is a specialised compiler driver that uses the open-source LLVM compiler infrastructure as its back-end. In contrast, LLVM is a flexible compiler framework rather than a ready-to-use compiler like NVCC.

CUDA Compiler (NVCC) Link to heading

Driver Program: NVCC is a driver that manages the process of compiling CUDA C/C++ code. It separates the host (CPU) code from the device (GPU) code.

Toolchain: NVCC is a toolchain, which uses a host C++ compiler (eg GCC/Clang on Linux) for CPU code, and an NVIDIA-specific internal compiler (eg CICC) for GPU code (PTX & SASS).

Fat Binaries: NVCC typically produces “fat binaries” that include both the host executable and the compiled GPU code, often with multiple versions for different GPU architectures.

LLVM Link to heading

Framework: LLVM is a collection of free, open, modular and reusable compiler technologies, libraries, and tools, designed to build a wide variety of compilers and language toolchains.

Intermediate Representation (IR): LLVM IR is a machine-agnostic “middle layer” that acts as the universal link between front-ends (C++, Go…) and ISA back-ends (x86, ARM…).

Optimization: The LLVM optimizer applies various performance enhancements (like loop unrolling and dead code elimination) to the IR, regardless of the source language or target architecture.

It is worth noting that LLVM can compile CUDA: the Clang front-end (part of the LLVM project) can handle CUDA code with the LLVM PTX back-end, without requiring the nvcc driver.

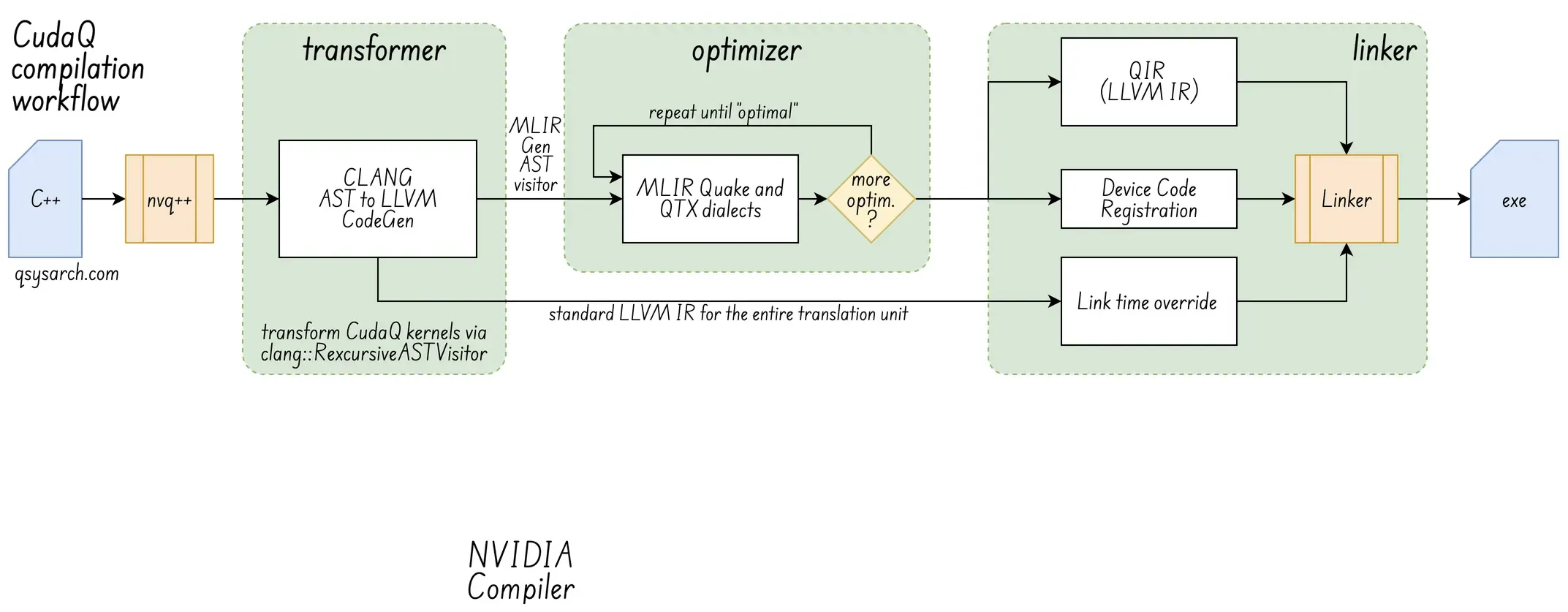

Triton Compiler Architecture Link to heading

The Triton language is a powerful Python-based Domain-Specific Language (DSL) designed to help create high-level vectorised algorithms that can be compiled to efficient parallelised code for GPU targets.

This is an example of the simplest kernel, which loads data from a memory block and writes it into another block. The value of offsets is [pid*BLOCK_SIZE….(pid+1)*BLOCK_SIZE-1]. The magic, which is not shown in this snippet, is that Triton can efficiently operate on the vector v, such as by doing math ops.

import triton.language as tl

@triton.jit

def move_kernel(in_ptr, out_ptr, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr):

pid = tl.program_id(axis=0)

offsets = pid * BLOCK_SIZE + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE)

v = tl.load(x_ptr + offsets)

tl.store(output_ptr + offsets, v)Triton is not limited to 1D vectors, and can cope with more dimensions using tensors. For example:

import triton.language as tl

@triton.jit

def load_2d_tensor( input_ptr, output_ptr,

stride_row, stride_col, # Stride of the input tensor (elements per row, elements per column)

M , N , # Number of rows and columns

BLOCK_SIZE_M,BLOCK_SIZE_N, # Block size for rows and columns

):

# X and Y tile position

pid_m, pid_n = tl.program_id(axis=0), tl.program_id(axis=1)

# Ptr in memory based on the stride

base_ptr = input_ptr + (pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M * stride_row) + (pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_N * stride_col)

# Offsets for X and Y indices

offs_m, offs_n = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M), tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

offsets_2d = (offs_m[:, None] * stride_row) + (offs_n[None, :] * stride_col)

# 2D loading ...that's magic!

loaded_2d_tensor = tl.load(base_ptr + offsets_2d)

return loaded_2d_tensorCompared to CUDA, Triton can be seen as a higher-level abstraction, dedicated to building neural network kernels (thanks to the tensor block approach), and that can generate efficient vectorised and parallel GPU code. Triton also support multiple backend GPUs:

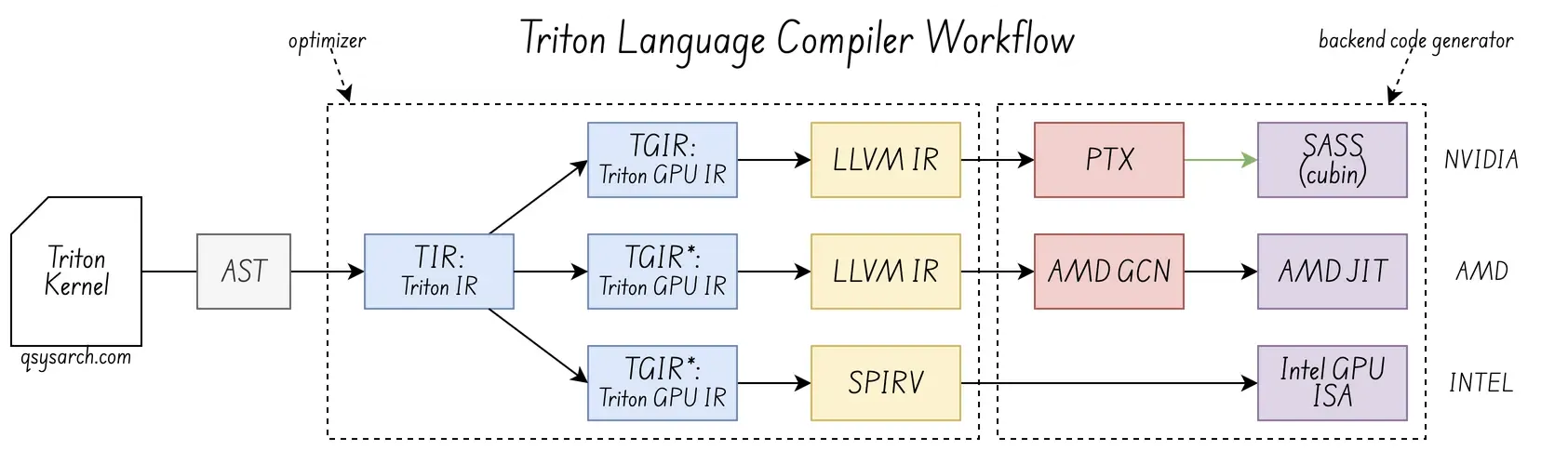

Triton does not use its own language parser. Instead, it relies on Python’s runtime and AST, then converts that AST into its own intermediate representations, TIR and TGIR, before generating GPU code. The link between the CUDA backend compiler and the Triton front-end compiler is the universal LLVMIR, and for Intel GPUs it is based on SPIRV (although I am unsure if TGIR is directly lowered to SPIRV, rather than going through the intermediate LLVMIR)

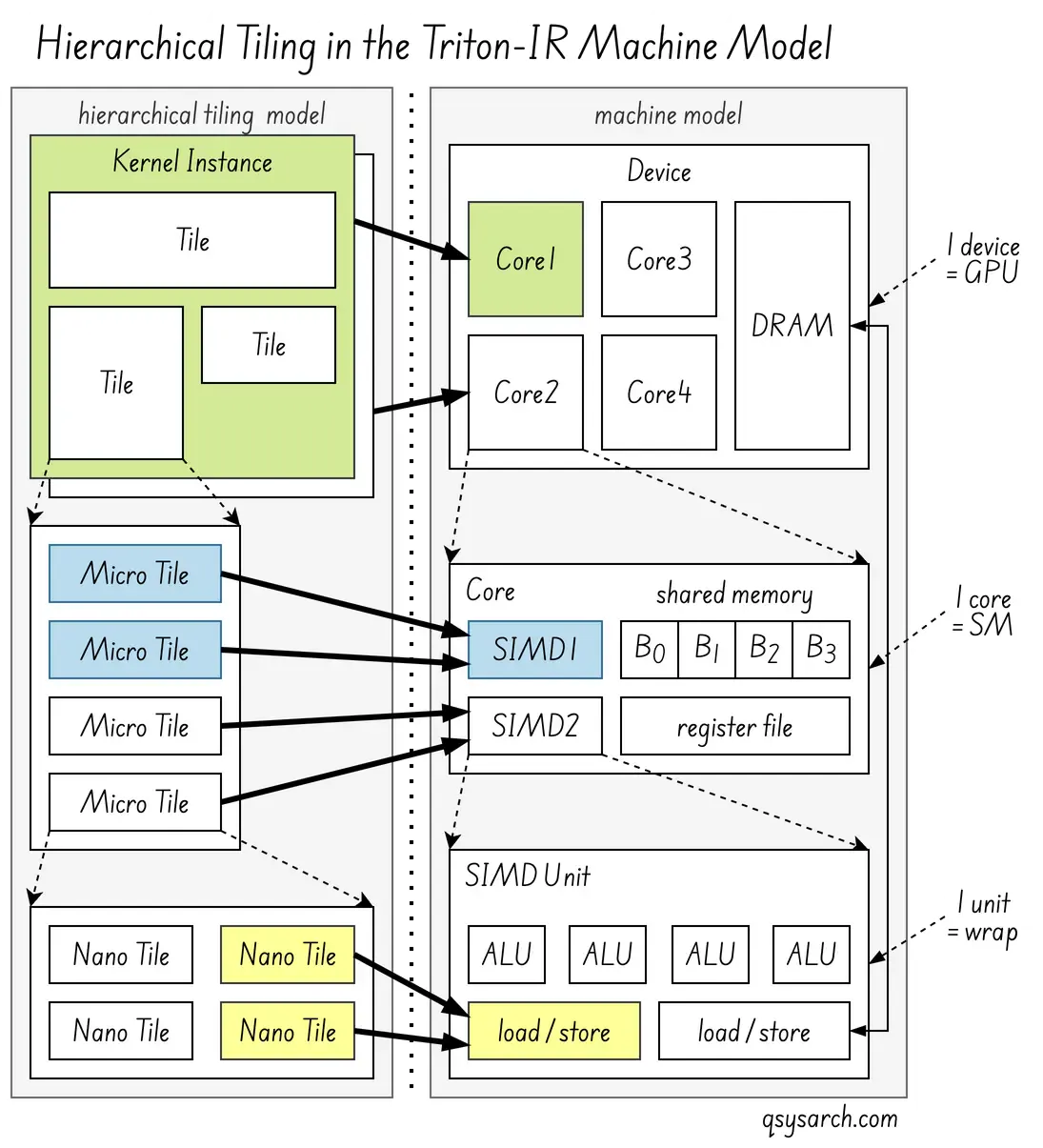

Tiling Link to heading

I wrote “vectorised algorithms,” though the core concept is more focused on tiled, block-level models:

Tiling is the primary mechanism. Triton’s mental model revolves around programming operations on small, statically-shaped multidimensional subarrays, or “tiles,” which the compiler automatically parallelises across GPU cores.

Tiling is the primary mechanism. Triton’s mental model revolves around programming operations on small, statically-shaped multidimensional subarrays, or “tiles,” which the compiler automatically parallelises across GPU cores.

Vectorisation, seen as loading/storing multiple data elements in a single instruction, is an optimisation: the compiler uses it as a key internal optimisation strategy to efficiently implement these tiles on the underlying hardware. This concept aligns with the nested tiling strategies (see the figure on the right), which aim to decompose tiles into micro-tiles and eventually nano-tiles to fit a machine’s compute capabilities and memory hierarchy as tightly as possible.

Triton Language Lowering stages down to Streaming Assembly Link to heading

Let’s have a look at how the high level tt.load triton language instruction is lowered down to SASS.

(For the reader: The code below is pseudo code, and does not work as such)

Triton IR (TIR) Link to heading

The initial stage, after parsing the Python AST, is the machine-independent Triton IR (TIR, an MLIR dialect). At this level, a tt.load operation is defined on a tile, and the tt.load operation is a high-level, unoptimized instruction that expresses a memory load of an entire tile. The tile can be a single array, but can also be a 2D array, or even one with any dimensions.

// simplified, illustrative TTIR fragment for 2 dimensionnal array

// load of 32 bits floating point values (without masks)

%ptrs = ... : tt.tensor<MxN, ptr<global f32>>

%vals = "tt.load"(%ptrs) : (tt.tensor<MxN, ptr<global f32>>) -> tt.tensor<MxN, f32>The high-level tt.load operation on a tensor pointer and a block of data (tile). The first input parameter %ptrs is tensor (n dimensions array) represented by tensor<MxN, ptr<global f32>>. It returns a tensor of the same dimension, but with values instead of pointer to values.

In practice, the tt.load also takes a mask and default value parameter, which is neeed for reading from the boundaries of the memory (in case the vector dimensions are not aligned on the stride).

%ptrs = ... : tensor<MxN, ptr<global f32>>

%mask = ... : tensor<MxN, i1> // in-bounds mask (optional)

%fallback = constant 0.0 : f32

%vals = "tt.load"(%ptrs, %mask, %fallback) : (tensor<MxN, ptr<global f32>>, tensor<MxN, i1>, f32) -> tensor<MxN, f32>Triton-GPU IR (TTGIR / TGIT) Link to heading

In the next stage, the Triton-GPU IR is used to convert generic tensor layouts into layouts that are hardware-specific, especially with regards to the memory layout and distribution across threads and warps. In other words, TGIT expends the n dimensionnal load into per-thread vector load ops that are easier to lower to LLVM.

// TGIR (illustrative)

%vec_ptr = tt.get_contiguous_vector_ptr %ptrs, vec_len=4

%vec_vals = ttg.load.global.v4f32 %vec_ptr // a vectorized 4-wide global load

%vec_vals_cast = f32x4 -> f32 // unpack to tensor<MxN, f32> shapeLLVM IR (LLIR) Link to heading

The Triton-GPU IR is then converted into per-thread instructions represented in LLVM IR. This low-level IR closely represents the final machine instructions and uses standard LLVM operations like pointer arithmetic, memory loads, and synchronization primitives. The tensor abstraction is largely gone, replaced by individual memory access operations for each thread.

// Example LLVM IR snippet (conceptual)

%thread_ptr = getelementptr inbounds float, ptr %base_ptr, i64 %thread_offset

%value = load float, ptr %thread_ptr, align 4Representation: The tile load is broken down into a series of individual load instructions with pointer arithmetic for each thread’s specific data element(s), and possibly shared memory operations if shared memory was used as a staging area.

PTX Assembly Link to heading

When the LLVM backend targets the NVIDIA GPUs, the next step is to lower to PTX. The LLVM load instructions are directly mapped to corresponding PTX load instructions.

// Example PTX snippet

ld.global.f32 %r1, [%thread_ptr]; // Load from global memory

// Or if staged via shared memory:

ld.shared.f32 %r1, [%shared_ptr];SASS Link to heading

Finally, the NVIDIA driver compiler (ptxas) converts the PTX assembly into SASS (Streaming Assembly), the actual native machine code executed by the GPU cores. As seen before, this step is usually done Just-In-Time (JIT).

// Example SASS snippet (conceptual, might involve specific opcodes)

MOV R1, ...

LDG.E.32 R1, [R0]; // Load from global memoryDeepSeek’s approach Link to heading

One thing worth noticing is that CUDA is a very convenient way to generate machine code for NVIDIA GPUs. Triton uses CUDA when lowering from PTX to SASS. The lowering to PTX is done from LLVM IR but requires libraries provided with the CUDA toolkit (e.g., libdevice.bc).

DeepSeek took another approach and opted for manual PTX optimisation: Custom PTX kernel helpers have been written by hand, treating PTX as the assembly language for the GPU. DeepSeek didn’t rely on a general-purpose compiler to generate this specific, highly non-standard code. Triton, on the contrary, being a generic language, uses the standard LLVM compiler back-end with the NVPTX target to automatically translate its intermediate representation (Triton-IR/MLIR) into optimised PTX assembly code.

DeepSeek took another approach and opted for manual PTX optimisation: Custom PTX kernel helpers have been written by hand, treating PTX as the assembly language for the GPU. DeepSeek didn’t rely on a general-purpose compiler to generate this specific, highly non-standard code. Triton, on the contrary, being a generic language, uses the standard LLVM compiler back-end with the NVPTX target to automatically translate its intermediate representation (Triton-IR/MLIR) into optimised PTX assembly code.

DeepSeek wrapper in csrc/kernels/utils.cuh using the mbarrier.try_wait instruction

DeepSeek wrapper in csrc/kernels/utils.cuh using the mbarrier.try_wait instruction

Why does this matter? Quoted from DeepSeek technical report: Specifically, we (DeepSeek) employ customised PTX (Parallel Thread Execution) instructions and auto-tune the communication chunk size, which significantly reduces the use of the L2 cache and the interference to other SMs. Does this mean that the LLVM NVPTX backend is not optimally efficient? To me, this means that there is room for further optimisations, but not only at the LLVM level, but also at exposing better bare metal ISA! It’s a win-win!

Conclusion Link to heading

Voila, this memo took once again longer time than expected. But this is a very much needed pre-study work before introducing the architecture of the Cuda-Q. I will update this post when it is ready.

(image credit: LLVM MOS)

(image credit: LLVM MOS)

References Link to heading

- Deep Seek using baremetal PTX

- Usable assembly language for GPUs : a success story

- Debugging Your CUDA Applications With CUDA-GDB

- What is Streaming Assembler? SASS

- NVIDIA H100 Tensor Core GPU Architecture

- Inside NVIDIA GPUs: Anatomy of high performance matmul kernels

- The process of a CUDA program compilation using the NVCC toolchain

- Deep Dive into Triton Internals

- A Deep Dive Into AMD Triton Compilation

- Triton Kernel Compilation Stages

- Textual Alignment in SPMD Programs

- Compilers and IRs: LLVM IR, SPIR-V, and MLIR

DrawIO diagrams used in this memo: